A long way to go

Students reflect on anti-Asian hate crimes and Stop Asian Hate movement

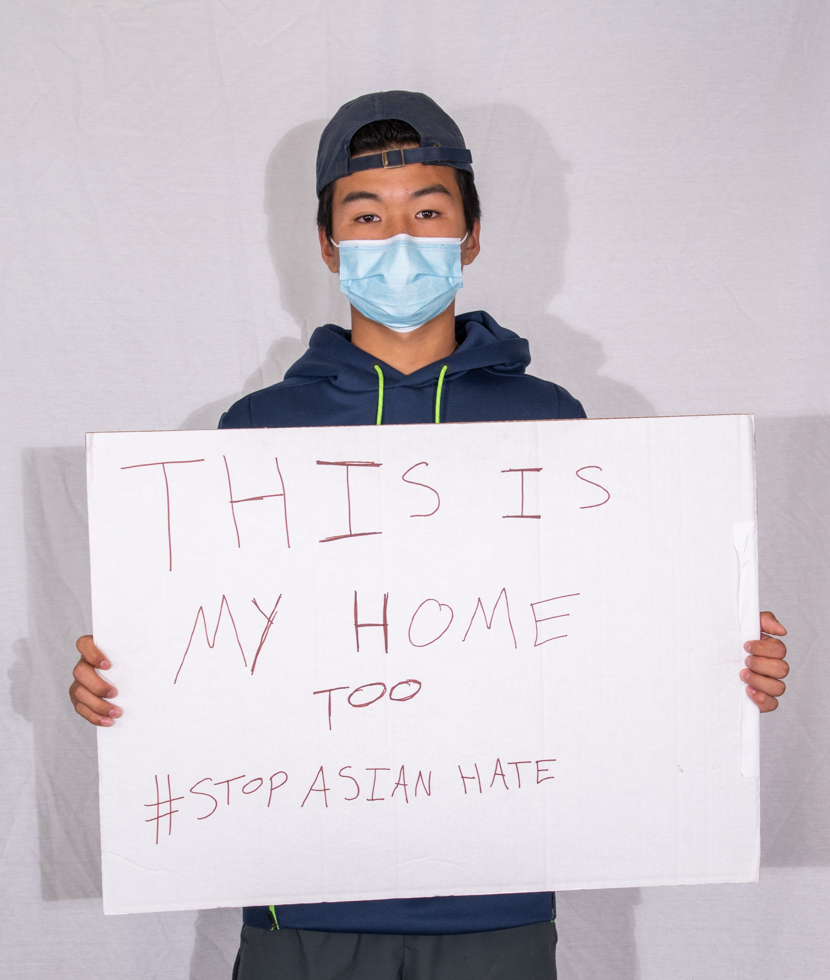

Photo by Aliyah Pratomo

Three students express their thoughts about the increasing hate crimes toward Asian American and Pacific Islander (AAPI) community in the country and the Stop Asian Hate movement that has been brought to light. From left: Nick Chenault (10), Ava Schmidt (12), Xu-Li Valadez (11). Photos by Aliyah Pratomo, courtesy of Ava Schmidt, courtesy of Xu-Li Valadez. Graphic by Aliyah Pratomo via Canva.

“Chinese flat face!”

The slur was thrown in the middle of Nick Chenault (10)’s soccer game when he was 12 years old. As a Korean-American, the insult didn’t make sense—but it was still hurtful.

“That’s one of the biggest things that has stayed with me throughout the past years,” Chenault said. “Knowing that even people around here, even little kids, have those things implanted in their brains.”

Chenault was not alone in facing discrimination as an Asian, even locally. Back in her sophomore year, Ava Schmidt (12) remembered how a substitute teacher assumed she didn’t understand English after looking at her. She recalled how the teacher talked slowly to her and even asked her friend if Schmidt needed a translator. At the time, she felt “belittled.”

“[You] definitely feel like you’re an outsider and don’t belong,” Schmidt said. “Even though that sounds really dramatic but in a sense you do feel like that, like you’re not treated the same even though you’re at school where everyone else is and we’re all the same.”

According to a report by Center for the Study of Hate & Extremism, anti-Asian hate crime in 16 of United States’ largest cities increased by 149 percent in 2020 with the first spike occurring in March and April amidst a rise in COVID-19 cases and negative stereotyping of Asians related to the pandemic.

During the infamous March 2020—when the school was shutting down due to rising COVID-19 cases in Michigan—Xu-Li Valadez (11) remembered how her classmates made several uncomfortable comments toward the Asian community such as “Kung-Flu.” She also recalled how somebody in her class blamed the virus on Chinese people.

Valadez felt “really angry” and “really hurt” when she heard these racist things said around her.

“It was just really uncomfortable,” Valadez said. “So I didn’t want to say anything because I thought that they would be like, ‘oh you’re overreacting’ and whatever. But I think now, if I heard somebody saying something racist like that I would definitely call them out.”

Since 2020, a more recent report still referencing the United States’ 16 largest cities saw a new increase of anti-Asian hate crimes from 149 percent to 164 percent. Common hate crimes and microaggressions toward the Asian American and Pacific Islander (AAPI) community include verbal abuse, use of racial slurs, attacking the elderly, being blamed for the virus and being targeted for race-based attacks.

“How can you do those things and feel good about yourself?” Chenault said. “After either giving somebody a weird look, or saying something to them, or not giving them business because of their race or how they look or anything. I’m just disappointed in society—it upsets me and frustrates me at the same time.”

The Atlanta-area spas shootings earlier in 2021 targeted three Asian-owned businesses and killed six women of Asian descent—which sparked the Stop AAPI Hate movement nationwide.

“I see [the Stop Asian Hate movement] as trying to go forward [and] trying to make things better,” Chenault said. “But at the same time, it’s more than just a movement—we’re trying to earn our rights back as humans and not be seen as these stereotypes.”

Although Valadez is in full support of the movement, she emphasized that discrimination against Asian people has always been happening.

“It took six people to die for people to realize that people are targeting Asian people,” Valadez said.

Schmidt feels that while the Stop AAPI movement is important and positive, she doesn’t hold infinite hope that it will bring change.

“It’s gonna happen and it’s gonna die down, and then that’s gonna be it,” Schmidt said.

In support of the movement, Schmidt signed petitions and engaged in conversations to raise awareness. Valadez joined a Stop Asian Hate rally in Lansing in late March. Chenault, who hasn’t joined any marches due to COVID, donated to protests instead.

(Photo courtesy of Xu-Li Valadez)

“I know if I can’t personally be there, I might as well do something and contribute to it,” Chenault said.

Valadez wished that people would understand that prejudice and racism come in different forms.

“It’s not all about just going up to an Asian person and pulling their eyes back or like saying ‘ching chong’ or whatever,” Valadez said. “It’s also the microaggressions that also get to me—like really helped fuel it.”

Chenault had more concerns that he wanted people to understand.

“Treat us like we’re an actual human,” Chenault said. “Not by our stereotypes or what you think we should be. We have standards too, we’re not just these calculators that just walk around and know everything. Get to know us first, then make your assumptions if you have to.”

In addition to Chenault’s statement, Valadez highlighted the harmful effects of the model minority myth.

“It’s really annoying because people think that the only reason you’re smart is because you’re Asian,” Valadez said. “It’s also really hurtful to just assume that all Asian people like ritually have money. That’s really hurtful to Asian people [with] lower income that [don’t] talk about their side.”

In the future, Valadez would love to see the school system talk about the events that have been happening, particularly about the Black Lives Matter and Stop Asian Hate movement

“I know especially with the Black Lives Matter movement, they [haven’t] really said anything about it,” Valadez said. “And they haven’t said anything about the Stop Asian Hate movement. So I feel like if they made an assembly or something about that for students that would be really cool. Or if the school system in general would include more stuff about minorities [in our curriculum].”

Valadez added that she thought all minorities have experienced some form of racism in their life.

“I really want white people to understand how hurtful they can be,” Valadez said. “Even other minorities can be hurtful to other minorities [and] I think we all just have to group together.”

Chenault expressed that as a country, Americans have “a long way to go.”

“I hope that we can hopefully get past these barriers and unite as one as we are supposed to be,” Chenault said. “Just knowing that we’re all humans. We all may come from different places, but we all can be one.”

![An infographic titled “Hear Our Voice” at the top followed by a question, “what do you want people to know and understand,” underneath. First row on the left, there is a portrait of Nick Chenault holding a sign which says, “This is my home too #StopAsianHate.” On the left, a quote by him is displayed which says: “get past the skin color and what we look like because underneath, we’re all just flesh and bones.” Second row on the right, there is a portrait of Xu-Li Valadez holding a sign which says, “Stop Asian Hate” On the left, a quote by her is displayed which says: “We can’t just be fit into one category, we’re like a whole race. We can’t just be [fit] into one little box of what you think we are.” Third row on the left, there is a portrait of Ava Scmidt. On the right, a quote by her is displayed which says: “There are so many different types of Asians, and so many different cultures within Asia. [Don’t] look at Asians as a whole and see us as more complex. I know I’m Chinese but a lot of times people just assume that [Asians] are Chinese [and] it’s just not true at all.”](https://eastlansingportrait.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/hear-our-voice-infographic.png)

Aliyah Pratomo is a member of the Class of 2023 and is on the Visual Team for Portrait. This is her first year on staff as a sophomore. Aliyah’s favorite...

Dheana • Jun 2, 2021 at 4:59 am

I find this absolutely true to stop AAPI hate in general. Thank you for an awesome report.