On April 8, East Lansing experienced a partial solar eclipse in the early afternoon, just before school ended. The eclipse began at 1:56 p.m., with partial totality occurring around 3:12 p.m., just after many students were dismissed for the school day. The eclipse ended at 4:25 p.m. Earth and Space Science teachers, Geralynn Jackson and Douglas Damery planned activities that involved the eclipse starting in January.

“The biggest part was [the] legal stuff, making sure that we had liability waivers and things like that, and then getting the glasses which was kind of tricky because they were running out by the time we got to the point where we were ordering them,” Damery said.

Purchasing the correct glasses required more effort than simply going on Amazon and placing the order. The school needed to make sure that the glasses were ISO-certified and that they were from a reputable company. Damery gave Assistant Principal, Ashley Schwarzbek the information for the glasses, and she coordinated the ordering.

“She originally ordered enough for our classes plus a few extras, and then went back and ordered enough for the whole school,” Damery said.

Schwarzbek felt that it was safer for every student to have a pair of glasses since the eclipse was happening right after school.

However, not all students watched the eclipse from East Lansing. Ele Salvador (10) traveled to Toledo, Ohio to be in the line of total totality, which lasted for about two minutes. Salvador watched this phenomenon in an open field off the freeway for the best view.

“We were in a field between Chipotle and I-75, but there were a lot of people there also,” Salvador said.

About three hours south from East Lansing, Heather Mueller, a science teacher, traveled to watch her second eclipse. She hopes to see the next one as well. Like Salvador, she also wanted to see totality.

“Before it becomes completely dark, it’s almost like you’re in a movie theater where they begin to turn down the lights and it just kind of goes, and then the whole sky turns dark,” Mueller said. “It looks like nighttime.”

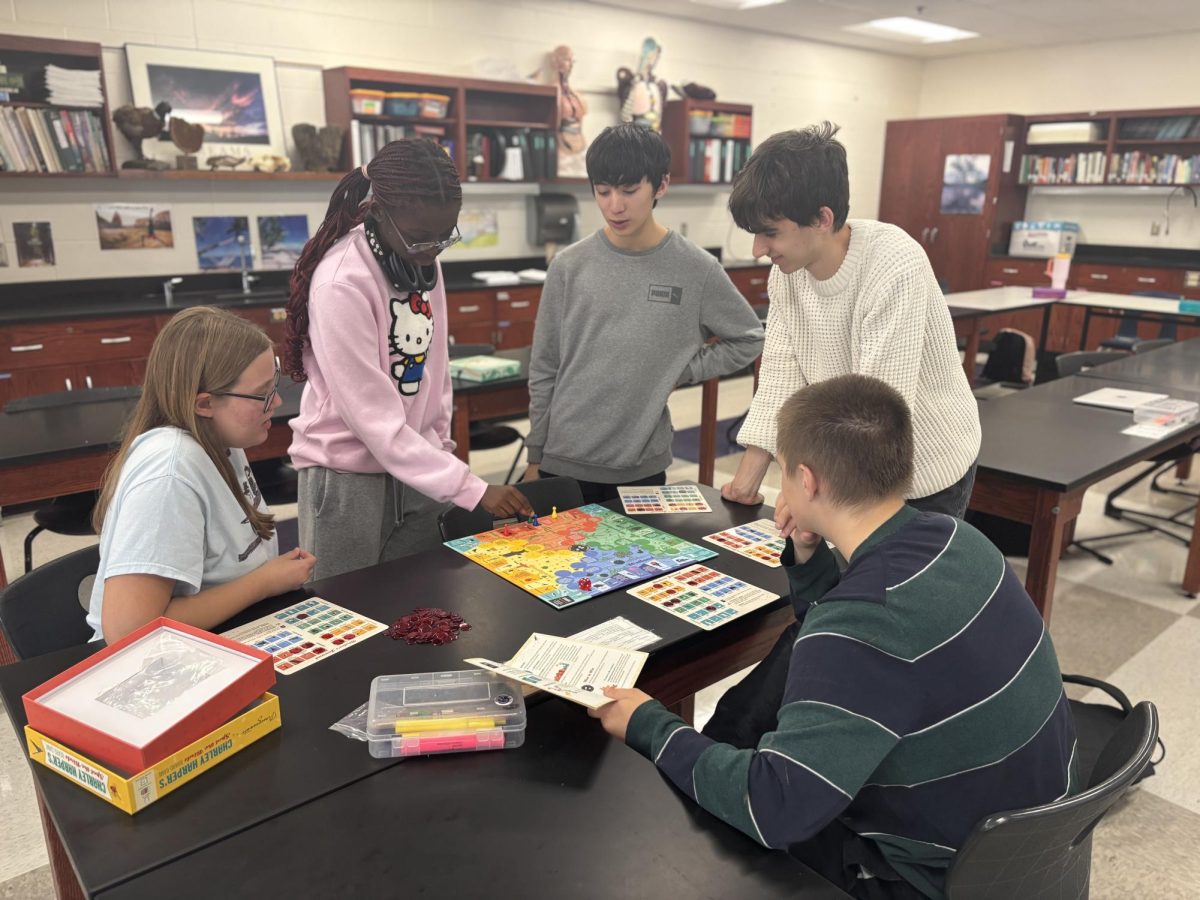

Still, most students did not travel to see the full eclipse. Instead, they stayed home and watched from the football field which was one of the activities that Jackson and Damery planned. While on the field students wanted to capture the moment, impelling them to get increasingly creative. Because students were discouraged from pointing their cameras directly into the sun, since it could damage the sensor, students found ways around this problem.

“What [one of my students] did was he put a magnifier on the outside of his phone and between his case, and then he borrowed someone’s glasses, so he could take a picture of the eclipse,” Jackson said. “That was clever.”

Both Jackson and Damery went through lots of work and planning so their students would have a lasting memory of this phenomenon and a complete understanding of the science behind it.

“[In class] we talked about the basic geometry of an eclipse, how solar eclipses are different from lunar eclipses and how the sun will never come between the Earth and the Moon,” Damery said. “That’s not an eclipse, that’s called an apocalypse.”

Both science teachers felt that it was important to stress this eclipse because they hoped it would give them a lasting desire to learn and experience future solar eclipses.