As the daughter of two accomplished basketball players, Ariyana was immersed in the game from an early age. Her father played professionally overseas while her mother played at the collegiate level and went on to coach at high schools in the area. From sitting in the stands during her mom’s practices to riding the bus with the team on game days, Ariyana grew up on the court.

“I watched them play basketball all the time, so I feel like it’s kind of in my genes,” Ariyana said. “I kind of fell into it the same way they did.”

Ariyana was only 9 years old when she started playing for her elementary school’s co-ed team. Though the team was meant to be a fun outlet for kids to try basketball, her mom, Ashley James, saw more.

“It was very shocking to see how serious she took it,” Ashley said. “Once she makes up her mind to do something, it’s a wrap after that.”

So, when COVID hit two years later and many athletes took a hiatus, Ariyana and her father practiced nearly every day. Waking up early to go to the gym and running drills became part of her routine.

When she returned to her first game in eighth grade, she was a different player.

“I was blown away. I knew she was okay but I had no idea that she would come out like that,” Ashley said.

While Ashley marveled from the stands, Ariyana felt her improvement on the court. She looked forward to high school, where she could continue her progress.

But beginning her freshman year at Waverly, Ariyana felt isolated. The team wasn’t a good fit for her, making it difficult to enjoy the sport she had grown to love.

“I feel like there was a lot of jealousy and I didn’t really talk to anybody there,” Ariyana said. “There was drama all the time.”

On top of the negative environment, Ariyana began experiencing unfamiliar health issues. During her sophomore year, she noticed a small bump in her leg. Initially, she brushed it off, thinking she may have gotten a bruise from practice. But that seemingly harmless problem silently grew. During tryouts, she noticed that her energy– which had always been one of her strengths as a player– diminished.

“I would get super tired, even though I run all the time,” Ariyana said. “I thought I just wasn’t doing enough.”

So, Ariyana dismissed her pain and worked harder to improve her stamina. But by the first two minutes of the second game of the season, a wave of illness overtook her. Her family took her to Urgent Care where she was diagnosed with COVID-19.

“I had all these sicknesses and I didn’t know where they were coming from,” Ariyana said. “I think that the environment at Waverly was taking a toll on me also. I feel like I wasn’t in a place where I would get better.”

Her COVID diagnosis didn’t just impact her mental and physical health. It also masked a much more dangerous underlying condition that wouldn’t appear for nearly two years.

“She was just like, ‘Oh, I got this, this little [bump] right here [in my leg]. It’s not painful, but I can feel it.’ It was so minute and non-invasive that we forgot about it.”

Ariyana never expected to leave Waverly, but when her family had to relocate due to job changes, everything shifted. One moment, she was playing against East Lansing; the next, she was wearing their jersey.

Despite feeling nervous about the transition, she was welcomed by her new coaches and teammates. The transition to a positive team environment felt like a breath of fresh air, motivating her to improve both health-wise and on the court.

“I had coaches and people that kept pushing me to keep going,” Ariyana said. “And I think over time I just felt less tired because I was in an environment where I wanted to be okay.”

Throughout the season, Ariyana did her best to bring an uplifting spirit to every game. At Waverly, she rarely spoke to anyone on the basketball team, but at East Lansing, she flourished. Teammate Maddox Guerrant (12) noticed the shift immediately.

“Ari was always excited to play,” Guerrant said. “She has a really great basketball mindset—she’s a leader. Having her at the center of the team made everybody more comfortable, happier, and more excited to play.”

While the team had always gotten along in practice, Ariyana started making plans with teammates outside of basketball, which eventually grew into regular bonding events. By the end of the season, she was the glue that held the team together.

“She goes out of her way to make everybody feel included and happy,” Guerrant said.

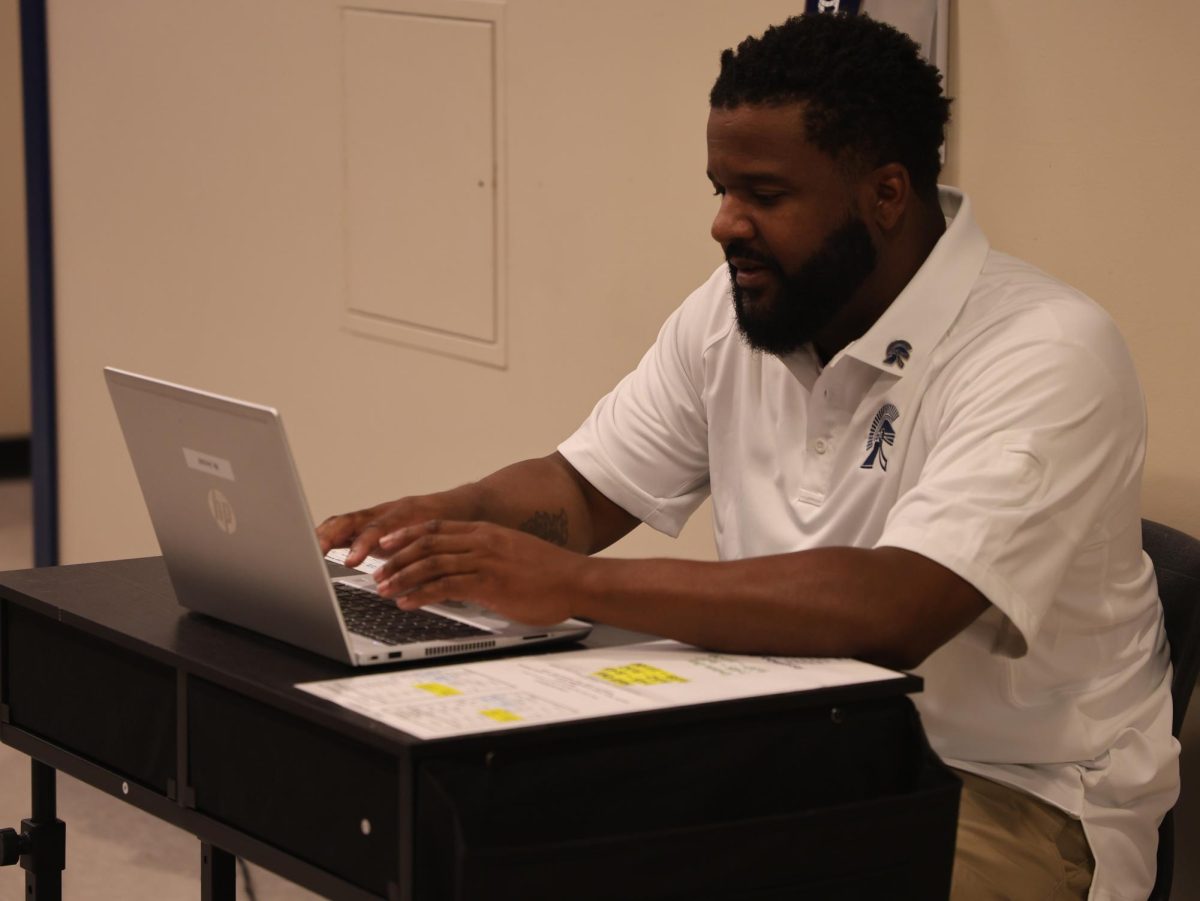

In March, Ariyana was named to the CAAC Blue All-League team. To honor her, the East Lansing basketball Instagram account posted a reel of her highlights from the season. The short clip caught the attention of college coaches across the country. After a Zoom call with Coach Chandler McCabe, Ariyana received her first Division I offer from Robert Morris University.

“Seeing all my hard work pay off made me feel good,” Ariyana said. “When I moved here, I didn’t know if I would get looked at because I was kind of late to the game—so it was great to see that I could still make it happen.”

Ariyana’s growth didn’t stop at the end of basketball season. She had done track since her freshman year as a way to take a break from basketball while staying in shape. But this year, the sport that had once been an afterthought became another beacon of her progress. During the season, Ariyana broke the 48-year-old school record in the high jump and placed third in the state championship. Despite gaining attention from colleges for her track performance, she kept her eye on the ball.

“It pushed me more in basketball,” Ariyana said. “I thought, ‘If you can do this in track, you can do this in basketball too.’”

At the beginning of the summer, Ariyana spent her time visiting colleges and playing basketball. With each campus visit, her excitement for the future grew. She was more certain than ever that she wanted to continue playing beyond high school.

“I was really excited, visiting actual schools and experiencing their environments was pretty cool,” Ariyana said. Going into my senior year, I felt way more confident about committing.”

However, as the weeks passed, Ariyana’s health began to decline. She hit her head during a club game and started experiencing intense migraines. As an athlete, she was used to injuries, so she took medication for the pain and waited for it to subside. But every time the headaches took a hiatus, they returned even stronger in the following weeks. By August, the pain was constant, yet she continued to practice. Her teammates never noticed anything was wrong.

“The last time I saw her was during summer basketball,” Guerrant said. “She wasn’t down. She was just her usual self. She seemed like Ari.”

It was Monday, Aug. 26, two days before school started, and Ashley dropped Ariyana and her brother off at the YMCA. Their dad would be meeting them there to run drills in the gym. It was a normal day.

“We had just paid for driver’s ed and finished our last rounds of shopping for school supplies,” Ashley said. “She was in a showcase that Sunday and had gotten her hair done for school.”

Ariyana warmed up with her brother, waiting for their dad to arrive. But as she began to run a lap around the gym, the familiar sounds of basketballs hitting the ground and shoes squeaking across the floor became deafening, echoing through her head as a wave of pain washed over her. Suddenly, her legs went numb. With each step, running became harder. She stumbled to the wall and sank to the floor, desperately trying to gather herself.

Her brother asked her if she was okay. She said she was fine, but she didn’t sound fine, something was off about her voice. He immediately called for their father.

Her dad offered her water and a granola bar, hoping her dizziness was a result of not eating enough that day. But within minutes, she began vomiting uncontrollably. They instantly knew she needed help, and checked in with Ashley before helping Ariyana into the car and heading to urgent care.

When they left the gym, Ariyana could still move with help, but by the time they arrived at urgent care, she could barely walk and had to rely entirely on her dad to carry her inside. A doctor began asking her routine questions, only to find out that she couldn’t respond.

“I tried to tell her I couldn’t talk, but my voice was slurring,” Ariyana said.

Ashley arrived shortly after as doctors attempted to determine what was wrong with Ariyana. But being young, they began testing for panic attacks and allergic reactions rather than considering the possibility of something bigger.

Ariyana remained in urgent care from 5 p.m. to 7 a.m. as doctors ran test after test. In that time, she lost complete control of her body and vomited so much that she needed an IV infusion. At first, she was in a panic, but exhaustion and pain quickly overtook her. At one point, doctors told her that the tests came back clear and she could go home. Ashley’s heart sank. She knew Ariyana wasn’t having a panic attack. Something was seriously wrong.

“I didn’t even know that they told me I was okay to leave, to be honest,” Ariyana said. “But I think I do remember my mom being really mad. She was like, ‘She can’t go home; she can’t walk or talk.’”

But by morning, they agreed that she needed to be admitted to Sparrow for further evaluation.

Ariyana couldn’t explain it, but she could feel her time running out in the ambulance ride to the hospital.

“I wasn’t talking. I was completely silent, and everything was just pain,” Ariyana said.

While Ariyana drifted in and out of consciousness, her parents finally received the answers they had been desperately seeking for almost 12 hours.

Doctors found three blood clots—two in her brain and one in her lungs. All this time, Ariyana had been having a stroke, and emergency surgery was the only option left.

“ [The surgeon] looked at me and said, ‘I’ve done this many, many times. I know what I’m doing,’”Ashley said. “And then I found out that he wasn’t even supposed to be at the hospital. He was supposed to be somewhere else. So for him to be a surgeon that does this particular thing with that particular machine, for him to be there was a miracle.”

The last thing Ariyana remembered before surgery was staring into bright fluorescent lights and listening to the muffled conversations of doctors as she slowly fell unconscious.

During this time, her dad called family members, and her mom made the difficult decision to wait at home where she prayed with hundreds of people from her church via Zoom.

“I think it’s important how you anchor your thoughts. And I knew if I stayed that my thoughts were going to be anchored in bad news,” Ashley said.

When Ashley returned to the hospital, the waiting room was filled with over 60 people, from family members to coaches to friends.

“It was surreal, especially for them to have the energy that they had. There was no sadness in the room. There was no worry. You didn’t have people doubting anything,” Ashley said. “I didn’t know she had that type of impact. I think it shocked her too, just seeing all the love. People don’t necessarily wear their heart on their sleeve all the time, and you don’t always know how much they care about you.”

After an hour and a half, hospital personnel delivered the news that Ariyana’s surgery was successful. And though this came as a huge relief, her journey was far from over.

Ariyana spent the next four days in a medically-induced coma. Doctors tried to wake her three times, but she didn’t respond to their efforts, leaving her family and friends in a whirlwind of uncertainty and fear.

“You don’t know if they’re going to wake up and be the same, you don’t know how serious the impact was, you don’t really know anything,” Ashley said. “I’m thankful for her father because he was able to bite the bullet for both of us. I couldn’t sleep at the hospital. I couldn’t be in the room without breaking down. It was like being in the worst part of a movie.”

At practice, the team that Ariyana had once filled with light fell silent with shock. However, despite their sadness, they came together to support her as much as possible.

“It was super quiet,” Guerrant said. “I think everybody was uneasy about the unknown, but we all stuck together and immediately started coming up with ideas of how we could support her.”

It wasn’t just the basketball team looking out for her. During this time, Ariyana and Ashley received more than a thousand text messages—some from people close to her, others from those she barely knew.

“The principals at East Lansing, the athletic directors, coaches, and so many students personally texted and checked up on her,” Ashley said. “Thousands of people reached out via social media. People also sent [gifts]. We had to move out of Sparrow. It felt like she’d been in college for a year—that’s how much stuff was in that room.”

Ariyana woke up on Sept. 1, four days after her surgery. The first person she saw was one of her nurses, Joan, who informed her family. Ariyana was unable to speak, form sentences, breathe without a ventilator, or swallow food—trapped in a world of silence, darkness, and fear. Though her mom tried to explain what was happening, there was no way for her to fully understand.

“I had to reassure her as soon as she opened her eyes, like, look, this is temporary,” Ashley said. “I didn’t tell her she had a stroke. I did not say that to her, probably for weeks, because I had a hard time saying it.”

But as Ariyana slowly regained consciousness, a light formed inside her. In the five days she was awake but unable to speak, she was alone with her thoughts. In those moments, she prayed, and eventually, she began to feel like herself again, finally realizing how much the blood clots had changed her before surgery.

“I really didn’t have any emotions whatsoever,” Ariyana said. “I was always lying down, and that was all I could do. I just remember feeling discomfort, and I was frustrated with how I was feeling. But after I had my surgery, I felt emotions again.”

As she began to show signs of improvement, doctors moved her into rehabilitation. With practice, she slowly but surely started to understand the words of those around her and find ways to nonverbally express herself. It was a painful but uplifting experience for her mom, whose relationship with Ariyana was built on strong communication.

“I’m the worst lip reader in the world, and she laughed at me a lot because I just couldn’t [figure] out the words,” Ashley said. “I had to spell out words. It was tough because I’m a good communicator, and everything we do is based on communication.”

By mid-September, Ariyana began three hours of physical therapy a day at Sparrow. While she slowly recovered, Ashley spent each night by her side, never missing a day. For Ashley, the goal was to support Ariyana mentally and make her life feel as normal as possible amid all the stress.

“We had daily devotionals, and I made sure that she stayed in contact with a specific group of people that could keep her motivated,” Ashley said. “Also making sure that she had little things to make her feel normal, like getting her hair done and wearing jewelry.”

On top of the support from her mom and the flood of love from those close to her, Ariyana also found comfort in the nurses at Sparrow.

A few days before being transferred, Ariyana was overcome with frustration. Just months earlier, she was a college-bound athlete, and now she was facing six months of rehab. As she cried with her mom, her night nurse shared her own story.

“Her name was Jocelyn,” Ariyana said. “She walked in while I was crying, so she was the only person who ever saw me cry. She told me about how she was in a car accident when she was 17 and lost her dad, and had to relearn how to do everything—just like me.”

At that moment, Ariyana’s fire, which had been on the verge of being extinguished, burned brighter than ever. Seeing someone who was once in her position showed her that recovery was possible.

After leaving Sparrow, she transferred to Mary Free Bed Rehabilitation Hospital in Grand Rapids, where her small steps of progress turned into significant bounds.

“Losing strength and having to relearn simple tasks like saying hi and bye was hard for me after a while because I’m like, this is not a dream, I really have to do this,” Ariyana said. “But [Jocelyn] kind of lit a fire in me. I still talk to her all the time—she’s like my sister now.”

In August, doctors couldn’t confidently predict whether Ariyana would be the same person when she woke up. But by the end of her hospital stay, she was walking, talking, and spending time with her teammates. She was discharged from Mary Free Bed on Sep. 28, a day before her 17th birthday. School staff partnered with her friends to throw her a party at the high school to celebrate.

“Mr. Lampi let some of my teammates and friends do a reunion,” Ariyana said. “That was actually pretty cool—to step foot in here when I hadn’t been in school for over a month.”

Ariyana returned to East Lansing with a strong mindset, ready to get back on the court with her team and return to normalcy in the classroom. But she knew it would be best to go slow. She began taking a few online classes and cheering her team on from the bench. She officially announced that she would be graduating with the class of 2026 to make up for the year she lost—a difficult but important decision.

“I want to ease back into it,” Ariyana said. “I’m used to getting all As, and I don’t want to throw myself back into something I can’t do. Even though basketball is getting better for me, and I’m constantly making progress, throwing myself into a basketball game wouldn’t be smart. So yeah, I think changing classes makes the most sense because I don’t want my senior year to be stripped from me.”

Ariyana has developed a newfound appreciation for small experiences she once took for granted and made it a priority to make the most of the rest of the year.

“I really just want to take advantage of everything,” Ariyana said. “I will probably go to every school event because I know what it’s like to just not be able to.”

Postgame

In November, Ariyana was invited to deliver the invocation speech at the Mary Free Bed Thrive Gala. As she stood on stage, she reflected on her journey. Soon, she would return to her seat, where doctors would express their amazement that just two months earlier, she had been in recovery, relearning the simplest tasks. Then, basketball season would begin, and she would find herself cheering from the sidelines instead of playing the game she loved. Eventually, she would have to watch in the wings as her friends graduated.

But in that moment, she thrived.

She had survived a stroke at 17. She had lost nearly everything, but now she was standing tall, using her voice to inspire others.

When her speech ended, no one remained in their seats.