Every day at 6 a.m. Amya Serrano (10) wakes up for school. She showers and enjoys a few moments of peace before waking up her 11-year-old brother. As he rolls out of bed, she goes to wake up her two younger siblings who are five and seven.

Their home is instantly chaotic. Her youngest siblings call her name all morning. Between doing their hair and getting them breakfast, she periodically bangs on the door to the bathroom she shares with her brother, attempting to hurry him along. She knows that with multiple children at many different schools, each with different start times, the chances of her getting to school on time are small.

This is frustrating for Serrano, knowing she will most likely be late to school each day. However, as the oldest sibling in the family, she feels a sense of responsibility to make sure that her siblings don’t have to experience this.

“Out of the whole house, I’m the oldest, so I have to wake up the earliest,” Serrano said. “But once I’m ready, there are still other people in the house who have to use the restroom and finish getting ready.”

Her family tries to shorten the time it takes for the younger children to get ready by laying out clothes and setting their school stuff out the night before, but it doesn’t always work.

“Sometimes it is not easy to remember to do everything at night,” Serrano said. “Those mornings are hard because I usually don’t get to school until second hour.”

Growing up, Rosie Cosper (9) saw visits to the doctor as a nice break from school, but once the appointments began overflowing her calendar, they impacted the way she lived her life.

At four years old, Cosper suffered her first concussion after slipping and falling in the bathroom. According to Boston’s Children’s Hospital, once a person has their first concussion, they are at risk for having more. Since then, she has had six more, mostly from playing lacrosse. Cosper also has Anemia, which stems from low iron levels in the blood. This has caused Tachycardia, the term used to describe a (resting?) heart rate of over 100 beats a minute. Each of these conditions requires medical attention, leading to as many as nine appointments a week for Cosper.

“Most doctor’s appointments are only available in the day,” Cosper said. “It’s super annoying because they all have to be during school.”

Throughout 2023 and 2024, Cosper attended physical, occupational, and speech therapy for her recent concussions.

“While I was in physical therapy for concussions, we discovered Tachycardia,” Cosper said. “Eventually we discovered the root cause of the Tachycardia was Anemia.”

Due to the timing of appointments available with her doctor, Cosper’s family has worked to make sure she can get the care she needs. Her dad, who works as an electric technician and a union president at the US Postal Office, decided to switch his schedule from working day shifts to working from 3:30 p.m. to 1:30 a.m. so that Cosper can make it to her appointments.

“My dad’s change in schedule helps me to get to my appointments, but not having him around after school five out of seven days of the week makes it harder to get to after-school activities and practices,” Cosper said. “It’s also hard when it comes to things like making dinner and other chores around the house, especially putting my baby sister to sleep.”

These stories are only of two students, but they represent a growing number of students who are late to class or absent more often than they wish to be.

After obtaining data from Bridge Michigan about ELPS’s chronic absenteeism rate from last school year, we asked Associate Principal Quiana Davis to run the numbers for the first semester of this school year. When she saw the number she was shocked–the number of chronically absent students was higher than she expected.

But when the chronically absent students were questioned, it didn’t surprise them at all. They thought it would be higher.

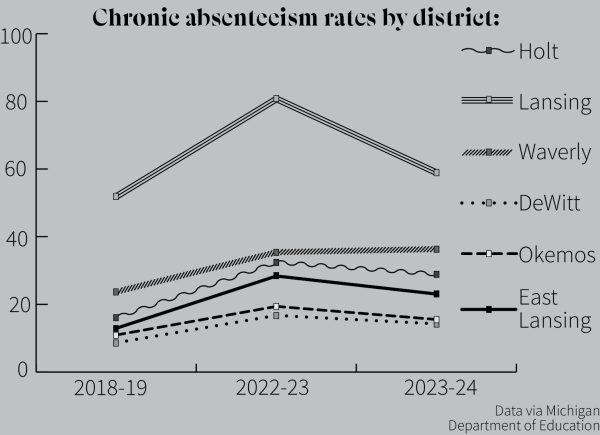

According to the American Federation of Teachers, chronic absenteeism is defined as missing at least 10 percent of school days (18 days total), excused or unexcused. Last year, about 30 percent of students in Michigan were chronically absent. In ELPS the rate was 23.1 percent. While this is lower than the average for Michigan, it is significantly higher than the rate of chronically absent students in the 2018-19 school year, which was 12.9 percent.

This is a concern for schools in the surrounding area as well. The Holt School District had a rate of 28.9 percent last year according to Bridge Michigan. Holt High School Principal Michael Willard reported that their administration considers this a problem and they are taking measures to fix it.

“We do a lot of communication out to families that students who we have identified as chronically absent,” Willard said. “We also have a support staff member who meets with students and their families when they have attendance issues.”

Willard believes there are many reasons that impact rates of chronic absenteeism, including anxiety, mental health, lack of success in school or transportation issues.

“To help, you need to understand what impacts each student so you can address how to support them specifically,” Willard said.

Last year, the Lansing School District faced a rate of 58.9 percent which is 21.9 percent lower than their data for the 2022-23 school year. According to the Communications Director of the Lansing School District, Ryan Gilding, several factors have impacted chronic absenteeism rates in their district. The factors included transportation barriers, housing instability, and economic challenges. The COVID-19 pandemic especially exacerbated these factors.

“During that time [COVID], many students became disconnected from in-person learning, and some are still working to re-engage with their studies,” Gilding said.

For students like Serrano and Cosper, many of their absences are outside of their control. However, for others, absences come from personal choices rather than urgent reasons.

Gerrit Garcia (12) attributes his absences to being stressed by hard classes and choosing to take days off for his mental health.

“When I take off days, it’s mostly to get caught up on other classes and prioritize them,” Garcia said.

Additionally, JJ Keesler (10) takes his absences as time to catch up on the sleep he misses out on due to the many extracurricular activities he participates in.

“There would be nights I didn’t get home until 12 or 1 [a.m.], and then I come home and just be exhausted and not have enough motivation to get up the next morning,” Keesler said.

Still, many students believe they can be successful, even if they miss school frequently. For Serrano, communication with her teachers is a big part of making sure she stays on top of her grades.

“Talking with your teachers has helped me a lot,” Serrano said. “When they understand what’s going on they’ll do their best to help you.”

There is not much Serrano or her family can do to change this trend immediately. She plans to keep helping with her siblings and staying on track for her success.

“It is hard but my plan is just to stay on top of it,” Serrano said.

Missing school is difficult for Cosper. She feels as though balancing missing schoolwork and doctor’s appointments makes her miss out on experiences at school.

“When I come back, I have a lot to do and I also miss hanging out with my friends and the in-school things we do,” Cosper said.

As a freshman, Cosper hopes to find ways to move her appointments to after-school, but this spot is often reserved for priority patients who can’t leave work early to make appointments.

“The priority spot is for people who physically can’t make an appointment during the day, so we’re just trying to find a way to get the appointments after school so I don’t have to worry about missing school anymore,” Cosper said.

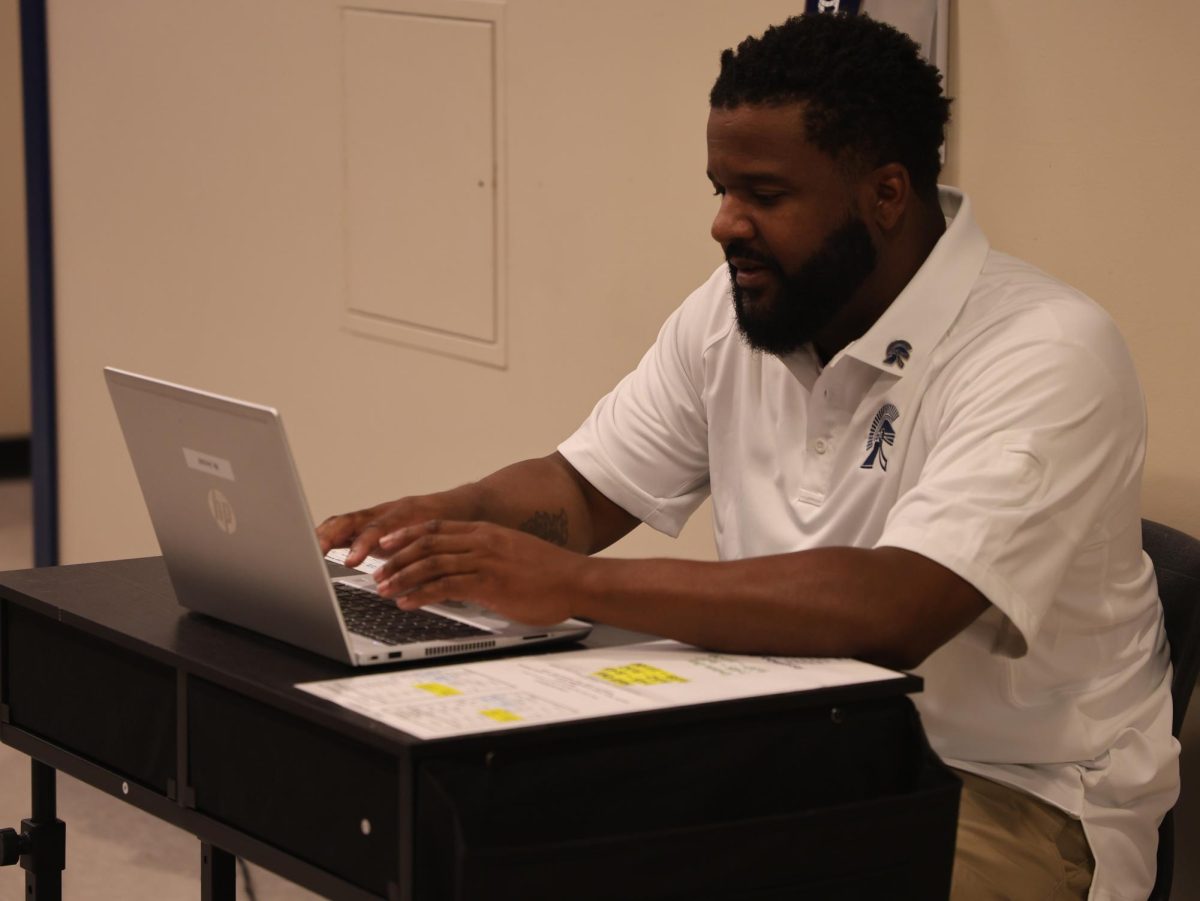

ELHS administration recognizes that chronic absenteeism is a problem not only across the country but in ELHS as well. According to Davis, it is a focal point of the administrative team. This year, they have worked to identify root causes through a data review process and investigated how to provide support for students who have barriers coming to school.

While each case is different, the more that students become accustomed to not showing up, the more the cycle continues. According to Associate Principal Jeffrey Lampi, administration is looking at enforcing stricter rules surrounding attendance in the future.

“We are looking to tie attendance to privileges like spectatorship, clubs, athletics and extracurricular activities,” Lampi said. “Once a student reaches a threshold of some absences- yet to be decided- they would be no longer allowed to participate in their extracurricular activities.”

The Lansing School District has implemented an approach, containing many different levels to address the issue of chronic absenteeism. They monitor trends across the schools to catch patterns before they begin to set in. Additionally, they have supplied students with gas cards or CATA bus cards to eliminate transportation barriers.

“For students who are struggling with attendance, we engage in proactive outreach—connecting with families to better understand and address any underlying issues that may be contributing to absenteeism,” Gilding said.

Administration understands that certain barriers that prevent children from getting to school are not easily solved, but they are committed to working with students who fall into these categories.

“We know that the only way to combat this issue is to work with each other,” Lampi said. “Administration is very willing to work with students and families on that route because we want students here.”