The toll of tardiness

New attendance policy addresses late students

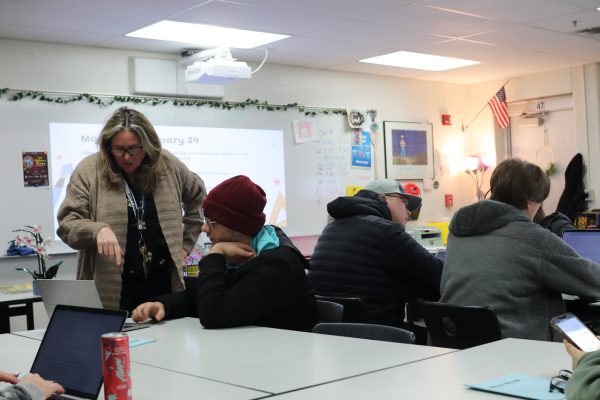

Photo by Adan Quan

Sitting down for their first hour, Earth and Space Science in room 421, Pryderick Achuonjei (11) and Auden Danowski (11) wait for class to start as students start to trickle in after the 7:45 a.m. bell announced the official start of first hour on Feb. 4.

February 12, 2022

Starting in January, administrators implemented a new attendance policy meant to combat tardiness. Included in the policy were instructions for teachers taking attendance and new punishments for students who are tardy more than 20 percent of their classes in one week, meaning a tardy in seven out of 33 classes. This is an amount that Associate Principal Quiana Davis labeled “chronic tardiness.”

An email sent to teachers and parents on Jan. 18 also included clarifications about passes and expectations for students.

“[Chronic] tardiness affects the school [by increasing] hallway traffic and classroom disruptions,” Davis wrote in an email to Portrait.

According to the policy, students who violate the policy will receive detention on Thursday after school. If a student does not show up to the detention, they will be signed up for the next detention. Missing the rescheduled detention results in an out-of-school suspension lasting one day.

The decision to make detention a consequence is based on the idea of taking time outside of class if class time is missed and because administrators wanted to offer grace, since the original policy involved course failure. Students were also given support resources and parents were given a chance to meet with the school to address the root causes of tardiness.

When asked for data about tardies for the first semester, high school administration requested more time to discuss the information internally.

In order to enforce this policy, teachers are asked to take attendance in the first 15 minutes of class, and for that attendance to be “accurate.” This attendance policy, however, is made flexible for students who aren’t able to get around as fast, such as Corinne Neil (10), who said that her teachers were understanding of her broken foot. Neil also pointed out that many students tend to be late to their first hours for various reasons.

“Like a lot of students can’t drive themselves and have parents or guardians take them to school,” Neil said. “When you have busy parents trying to get up and get ready, take multiple kids to school in some cases it can be hard to be on time every morning.”

But she does believe the policy could help students for the rest of the day, when they’re already in the building.

“I feel it can help with time management,” Neil said. “I walk from orchestra to English and it will definitely keep me on task to get to the other part of the building.”

Attendance is also important to being able to understand content in class. The importance of attendance to receiving proper instruction is something that teachers are familiar with. Timothy Akers, an English teacher, believes attending class on time is important for all students.

“50 percent of success is just showing up,” Akers said. “Being present is vitally important for anything, you know, especially in a class where it’s discussion-oriented. I may cover something that students missed out on and then it might cost them later.”

And while a tardy can seem like a small issue in the long run, it can have detrimental effects on learning if it happens several times. According to interviews with several teachers who did not want to be named as to not appear to be critiquing the policy or high school administration, the problem of tardiness is most egregious in first hour. Teachers such as Akers have experienced up to half of their class roster showing up more than five or 10 minutes late to first hour, and point out that being late doesn’t just affect the late student.

“It’s starting to stretch into the point where it’s becoming burdensome for teachers to deal with, you know, having to go back over instructions that were given or fill in the blanks,” Akers said.

Teachers who talked with Portrait about the policy were not sure about whether it was being enforced, and several did not notice any major changes in attendance based on observations. Akers, however, did notice that some students who were “habitually late” after lunch were starting to make noticeable effort to get to class on time. He acknowledged that the change could be due to the new attendance policy, or his own participation grades, which are affected by tardies and unexcused absences.

Akers also pointed out that instating a new attendance policy half-way through the year could be less effective than at other times, but agreed that there was a problem with tardiness.

“I don’t know, if you know, doing it mid-year is the best idea because kids have already, especially during a pandemic, the kids have already established habits, but there still has to be some kind of accountability.”

While teachers recognize students have to get to school for first hours and can have obstacles on their way, teachers like Akers believe tardies are important to accountability and building skills important to life.

“If you are absent because you’re having issues with transportation or something you’ll learn to advocate for yourself by talking to the teacher whose class you’re absent for,” Akers said. “Or, if it’s something habitual, you need to communicate that to the teacher and see if there’s some kind of resolution. But just showing up late, that’s not a good habit to establish.”

Davis hopes that enforcing punctuality will help students build positive habits later in life.

“‘Practice makes permanent,’ not perfect, so we want to help build positive skills for real world experiences,” Davis wrote.