From a new perspective

Teachers and students discuss why AP classes don’t reflect school-wide demographics

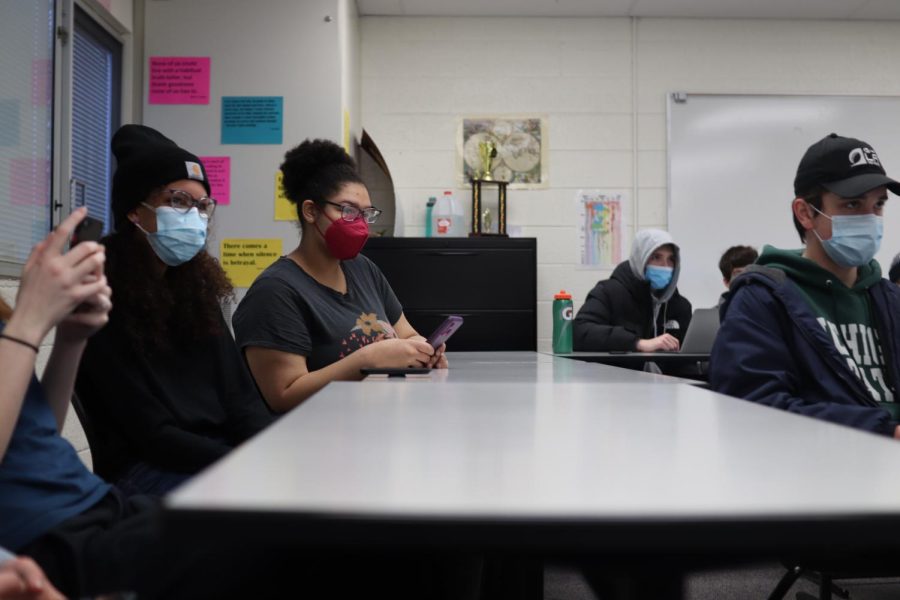

Photo by Natalie Seitz

Watching the board, Ky Bey (10) prepares for the AP World test on Feb. 9 during first hour in Mark Pontoni’s classroom. Bey is one of a few people of color in her AP World section.

For Ky Bey, it was another day in AP World History, listening to a lesson about European colonialism. As someone with family who have been victims of European imperialism, being from Senegal and the Democratic Republic of Congo, the topic is already challenging. But then the topic of the Belgian Congo came up— something that Bey had a personal connection to, since they have family from Congo.

They were discussing the atrocities committed there when one of Bey’s classmates made a comment that caught them completely off guard.

“I thought it would be worse.”

Immediately, they felt sick and confused. Exchanging looks with the only other person-of-color in their class, they realized they weren’t the only one experiencing confusion and disgust. The feeling became so intense that they ended up stepping into the hall for a moment.

“I just kind of felt like I didn’t understand how kids could be so detached and not really care that much and even say that they thought it would be worse,” Bey said. “I just, I don’t know. I just felt kind of really uncomfortable in that class.”

Their AP World History class only has three other people who are Black, according to them. And this skewed demographic is not uncommon in AP classes. Bey is unsure about why this could be, but personally, they believe that it could be because Black students think they will be discouraged from taking an AP class— something that has happened to her friends. Bey themself has chosen to not talk to teachers or counselors about their decision to take AP classes, because they believe that they will discourage them.

Bey’s class is not an outlier among APs as well. According to data from the school registrar, all AP social studies courses have a total enrollment of 299 students. And 223 of those students identify as white, with the rest making up various minority backgrounds.

Compared to the rest of the school, these proportions— about 75 percent white and 25 percent people-of-color (POC)— are noticeably different from the school’s population, which is 56.7 percent white and 43.3 percent POC. The percentage of white students ranges from 65 percent to 75 percent in all AP classes, with the disparity most visible in social studies and math APs and less visible in English and science APs.

Bey’s experience with the lack of diversity isn’t only apparent in social studies classes, and isn’t something that only they’ve experienced.

McKenzi McGill, a senior in AP Economics, AP Calculus AB and AP Language and Composition notices the issue, and feels that this issue could have something to do with the amount of support students of color receive at home. She expressed how the harder classes could be intimidating and challenging, which is why many students need some support to choose to take them and excel in them.

“I can see that not all the Black people in the school necessarily get the support that they need,” McGill said. So then it’s just like, okay, you’re just gonna stay in like, the basic level classes and it’s like, fine, because you’ll still graduate.”

As a veteran teacher, AP Literature teacher Emily Holmes felt that this issue could have something to do with a lack of confidence in the education system itself. She reported the number of students of color in her AP class fluctuates over the years, but her classes always remain predominantly white.

Additionally, she noted that her AP class has prerequisites, which keeps some students from being able to take it in high school. She believes that because Pre-AP classes are student selected, some who make the decision not to take them will often not want to take AP.

Holmes believes that Black students can provide powerful viewpoints on race-related topics discussed in class. While she does not expect them to do so, she appreciates their willingness to share.

“It is kind of wonderful when a student of color will speak up about their personal experiences,” Holmes said.

And as a newer teacher in the district, history teacher Mark Pontoni believes Black students and/or economically disadvantaged students could be discouraged from taking AP classes because of the time commitment and because of ideas about Black students in AP classes.

“A lot of students are forced to work to support their family. And then adding an AP load on top of that is not something everybody can do,” Pontoni said. “If people look at a class and go, oh, that’s not for Black kids. Then it takes a certain amount of courage for a black kid to sign up for it.”

Having obstacles in the way for students, especially obstacles that primarily affect POC, hurts the discussion in Pontoni’s classes. After teaching in a predominantly white district before he came to East Lansing in 2019, Pontoni feels that the diversity at East Lansing is beneficial to his classes.

“The diversity in the classroom is so important to me as a teacher because I can draw on experiences,” Pontoni said. “When I get an exchange student it’s a great thing. When I have students that were born in other countries that live here now, I can draw them and I do draw them into discussions.”

But he notices the relative lack of diversity in his classes, compared to the rest of the school. And according to him, it’s an issue that has not gone unaddressed by both the school and himself.

Most of all, Pontoni believes students should be in AP classes if they are likely to succeed, something that he doesn’t think is happening currently at ELHS. This means that students who should be in AP classes aren’t— a group that has a significant number of students of color— and that students who shouldn’t be in a class, tend to end up in one.

“One kid in a class that they don’t belong in and in terms of what they can achieve, I think is setting them up for disappointment,” Pontoni said. “I think we should be setting kids up for success. If you have people that can’t put a couple sentences together, they don’t belong. That’s my view. It’s very rare that you see a kid coming in at the beginning of the year super struggling with writing that goes on to have success in the class.”

While the school’s current policy is to allow any student to take an AP class— something called an open-door policy— Pontoni thinks it would be better to screen students before letting them take AP classes. What screening looks like depends on the school, but some require essays or a recommendation from a teacher. Pontoni would like it if the school required a writing sample— something that lets teachers pick students who can critically think as well as read and write well. But eliminating an open-door policy doesn’t have to mean decreasing diversity.

“Teachers, we do this all the time in terms of adjusting our teaching to individual students, that’s part of our job. If we know that a kid is struggling but we really want that diversity in our classroom, then we work harder with those kids in different ways to help. So it’s all doable. We do it every day.”

However, according to Director of Equity and Social Justice Klaudia Burton, one of the biggest factors that contributes to the issue is the current lack of diversity in the classes itself.

“Many students of color for many years have not seen themselves represented in those courses and therefore choose to not enroll in the courses themselves.” Burton said.

Whatever the reason may be, Burton knows that the lack of diversity has a large impact on learning in AP classes.

“When we don’t have a well rounded demographic in these classrooms it lacks the true depth of the school culture and what all students can bring into academic spaces,” she said.

This disparity is not a new issue. Lack of diversity in AP classes is an issue that is frequently brought up on a national level, and one that ELHS has taken steps to address. According to associate principal Ashley Schwarzbek, who oversees AP classes as part of her duties, administrators are introducing a new four-year planning program called Xello that will hopefully encourage more students of color to take AP classes. She hopes that it will allow for better conversation between counselors, teachers and students about what their plans are.

“I think when having those conversations when students are younger, it becomes a lot easier to let everybody try to place an AP class or so in here if that’s something that you’re interested in, see if that’s something that you still want to strive towards in this particular area.” Schwarzbek said.

Aside from Xello, the school has introduced multiple other strategies in order to increase the diversity of AP classes. Recently, they removed the Pre-AP requirement in some subject areas, and made it so that testing is not required in order to take an AP class in hopes of making the enrollment process less intimidating.

In the future, Bey hopes more people of color will take AP classes. In doing so, they hope that comments like those relating to the Congo will be less likely to happen. And, they believe that having classes that are more diverse will not only provide opportunities for students to take challenging classes— it will also allow all students to benefit from diverse voices. But for that to happen, attitudes and policies need to change.

“I’ve always had teachers and administrators think that I’m lesser than and that I can’t do as much compared to my counterparts and I just kind of feel like they’re already putting me on a lower pedestal than everybody else,” Bey said. “And I guess it’s at this point, it’s just mistrust and I’m too scared to talk to them, because I just don’t want to have to brace myself for that same reaction. Every time.”

Holyn Walsh is a member of the Class of 2025 and the Editor-in-Chief of Copy for Portrait. This is Holyn’s fourth year on staff as a senior. Holyn’s...

Adan Quan is a member of the Class of 2023 and one of the Editors-in-Chief of for Portrait. This is his third year on staff as a senior. He also reports...

Natalie Seitz is a member of the Class of 2022 and one of the staff writers for Portrait. This is her first year on staff as a senior. Natalie’s favorite...

ixchel • Feb 12, 2022 at 8:14 pm

the journalism that needs to be made. it looks great you guys, keep it up !!